Blog: Nowhere to Go – The Do Not Rent List

By Carrie Cyre

In June 2022, Post Media reported on a private Facebook group with more than 2000 members called “Landlords Beware! Bad Tenants — Edmonton and area” (Boothby, 2022a). A group of local landlords and property managers created this private Facebook group to share information about problematic tenants. The posts on this site list “problem” tenants accused of damaging housing or property, leaving items behind when moving out, and unpaid rent (Boothby, 2022a; Connolly & McCarthy, 2022). This group’s reported purpose is to warn other landlords about these tenants and blocklist their ability to rent in the future.

The Do Not Rent list can have far-reaching implications:

- Unofficial and unregulated lists like this can cause worsened low-vacancy, high-rent housing situations, and housing discrimination (Boothby, 2022c).

- These lists may violate individuals’ human rights to housing (Boothby, 2022c).

- Misusing and sharing private tenant information is against Alberta privacy laws (Connolly & McCarthy, 2022; Boothby2022b).

- Raising grievances on Facebook or any private social media space does not provide any mechanism for tenants to dispute claims (Connolly & McCarthy, 2022).

The Cost of Housing

Amid a nationwide housing crisis, many Canadians have difficulty finding affordable and safe housing. Commonly, individuals experience barriers like low vacancy rates, high prices, and discrimination (Auspurg et al., 2019; Ages et al., 2021).

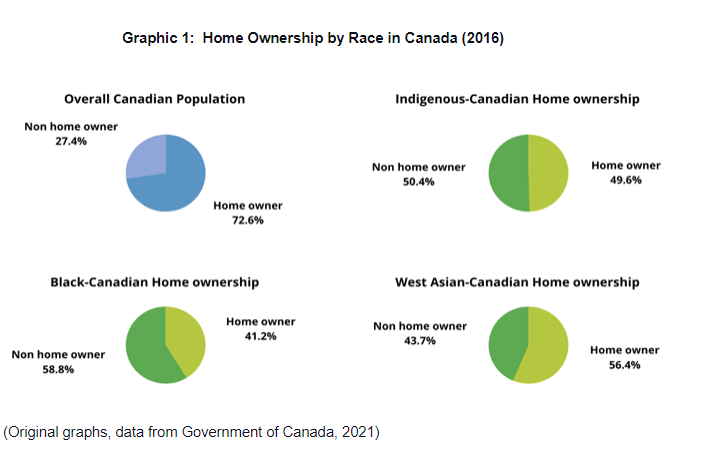

Buying a house

Canada has continually been among the most expensive nations regarding housing (Du et al., 2022). Even Edmonton, one of the more affordable cities in the country, has average single-family homes costing upwards of over $400,000 (Du et al., 2022). The high housing prices in Canada have led to lower ownership rates amongst Indigenous Canadians, Black Canadians, West-Asian Canadians, and many other racialized groups (Ages et al., 2021).

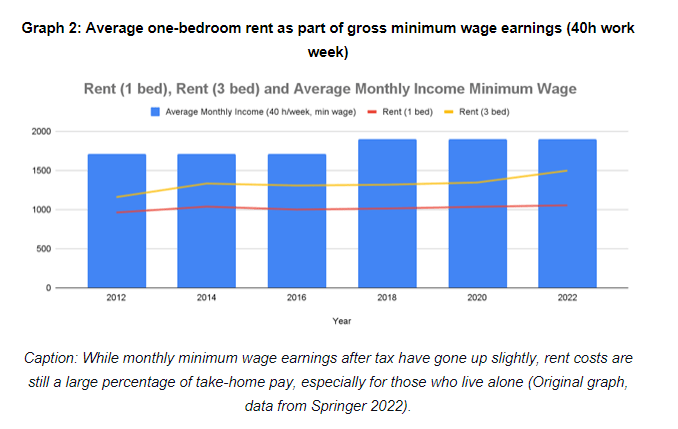

Renting

Canada’s rental increases over the past several years have significantly outpaced increases in the minimum wage (Springer, 2022). As a result, rent increases have disproportionately affected people living on fixed incomes, such as minimum wage workers, seniors living on a government pension, and those reliant on social services (Government of Canada, 2021).

The Do Not Rent list also violates the individuals’ human rights to a place to live by creating an unexpected barrier to securing safe and affordable housing (Boothby, 2022b). Many individuals have experienced discrimination when renting, including those who identify as Black, Indigenous, persons from the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, low-income individuals, single-parent households, immigrants and refugees, and persons living with a disability (Springer, 2022). In addition, the private rental market can discriminate against individuals by asking them to pay relatively higher prices to get the same housing quality as others or may provide substandard housing (Pager & Shepherd, 2008). Studies have shown that individuals from marginalized backgrounds can be especially vulnerable to housing insecurity and housing discrimination (Ages et al., 2021; Auspurg et al., 2019).

Government intervention is often suggested as a solution to housing insecurity, high rent, and low vacancy (Pasalis, 2022). Unfortunately, the Federal government discontinued funding for subsidized housing in 1993, and responsibility was transferred to the provinces (Perrault, 2022). Additionally, Canada has failed to allow enough changes to land zoning to allow more dense housing to be built (Pasalis, 2022). In Alberta, while subsidized housing is available, it does not meet the demand, and in 2021, there were over 25 000 Albertans on the waitlist (Government of Alberta, 2021).

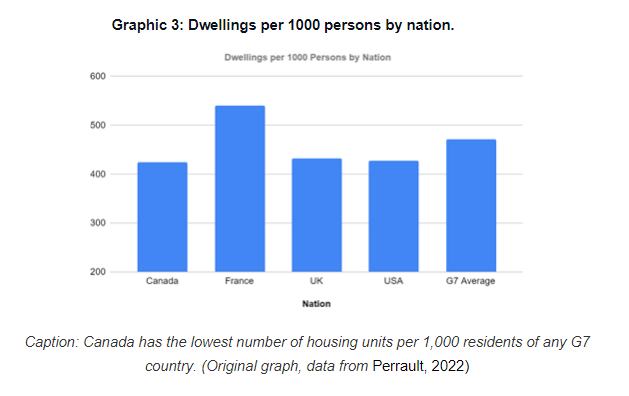

There is also a lack of housing in general across Canada. To compare Canada to other G7 nations, the average number of housing units is 471 homes per 1,000 residents across the G7 (Perrault, 2022). However, Canada has only 424 homes per 1000 Canadians, 10% lower than the G7 average (Pasalis, 2022). Further, Alberta has recorded the lowest number of private dwellings per capita relative to other provinces (Perrault, 2022).

The sharing of tenant information is against Alberta privacy laws.

A legal criticism of this Facebook group’s list is that these landlords misappropriate private data and share it without tenant knowledge or consent. This practice is illegal as it breaks Alberta’s Personal Information Protection Act (Boothby 2022b). Public Interest Alberta and the Alberta Privacy Commissioner’s Office are aware of this sharing of tenant information and are investigating.

Landlords already have the legal right to run credit checks and reference checks on potential tenants. (Government of Alberta, 2022)

Personal Information Protection Act, SA 2003 c P-6.5 also called PIPA. PIPA is the act that protects personal data in the private sector in Alberta. PIPA gives consumers the right to access their personal data held by an organization such as a landlord. PIPA also imposes certain requirements on how companies or organizations may use, store and share that personal information (OICP, 2022).

One final problem with the list is that there is no way for a tenant to be notified if they are on the list (Connolly & McCarthy, 2022). As a result, a tenant cannot share their side of the story or remove their information. Once someone realizes they are on the list, there is no process to have their information removed (Connolly & McCarthy, 2022). As outlined in the Alberta Tenancy Act, tenants and landlords have legal means to use when in conflict. However, Alberta housing advocates feel that legislators need to update the act to balance the power and responsibilities of landlords and tenants (Boothby, 2022b).

The Do Not Rent List controversy renews the call for action on the housing crisis. Advocates, academics, and government officials have suggested many solutions to address the housing affordability crisis (Canada Housing Crisis, 2021; Erl, 2022). However, as a lack of housing and high housing prices are complex problems, they require a great deal of public support, public funds, and coordination with many different levels of government.

While the Do Not Rent group page is shut down, at least for now, similar pages could resurface in other formats and locations. This current chapter in the ongoing Canadian housing crisis asks us to consider if it is fair to allow past rental problems, whether accurate, exaggerated, or fabricated, to prevent someone from accessing rental housing. If housing is a human right, whose responsibility is it to provide housing?

References

- Ages, A., Aramburu, R., Charles, R., Chejfecc, C., & Buhubesh, R. (2021). Housing Discrimination in Canada: Urban Centres, Rental Markets, and Black Communities. McGill School of Public Policy. https://www.mcgill.ca/maxbellschool/article/articles-policy-lab-2021/housing-discrimination-canada-urban-centres-rental-markets-and-black-communities

- Auspurg, K., Schneck, A., & Hinz. (2019).Closed doors everywhere? A meta-analysis of field experiments on ethnic discrimination in rental housing markets. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(1), 95-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1489223

- Boothby, L. (2022a). Edmonton landlords run ‘do not rent’ list with hundreds of tenants in private Facebook group. The Edmonton Journal. https://edmontonjournal.com/news/local-news/edmonton-landlords-run-do-not-rent-list-with-hundreds-of-tenants-in-Private-facebook-group

- Boothby, L. (2022b). Alberta privacy commissioner investigates complaint related to Edmonton ‘do not rent’ list. The Edmonton Journal. https://edmontonjournal.com/news/local-news/alberta-privacy-commissioner-investigates-complaint-related-to-edmonton-do-not-rent-list

- Boothby, L (2022c). Revamping Alberta renters’ rights and investigating Edmonton landlord group needed: advocate. Edmonton Journal. https://edmontonjournal.com/news/local-news/revamping-alberta-renters-rights-and-investigating-edmonton-landlord-group-needed-advocate

- Connolly, M., & McCarthy, T., (2022). Another do not rent list was made public in Edmonton. Radio broadcast: CBC Radio, Radio Active. https://www.cbc.ca/listen/live-radio/1-52-radio-active/clip/15923225-another-rent-list-made-public-edmonton.

- Du, Z., Hua, Y. & Zhang, L. (2022). Foreign buyer taxes and house prices in Canada: A tale of two cities. Journal of Housing Economics, 55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2021.101807

- Erl, C.(2022). The Homefront Strategy: Democratizing Housing in Canada. McGill Publications. https://www.mcgill.ca/maxbellschool/article/articles-max-policy/homefront-strategy-democratizing-housing-canada

- Government of Alberta. (2015). Personal Information Protection Act – Overview. https://www.alberta.ca/personal-information-protection-act-overview.aspx

- Government of Alberta. (2021). A New Approach to Housing. Housing and Community. https://www.alberta.ca/article-a-new-approach-to-housing.aspx

- Government of Alberta. (2022). Landlords and tenants. Housing and Community. https://www.alberta.ca/landlords-tenants.aspx

- Government of Canada. (2019). National Housing Strategy Act. Justice Laws Website.https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/n-11.2/FullText.html

- Government of Canada. (2021). Research Insight: Homeownership Rate Varies Significantly by Race. Housing Insight. https://assets.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/sites/cmhc/professional/housing-markets-data-and-research/housing-research/research-reports/housing-finance/research-insights/2021/homeownership-rate-varies-significantly-race-en.pdf?rev=af9ae04d-00bd-43ce-8619-d5e5d4a37444

- National Right to Housing Network. NRHN (2022). Right to Housing Legislation in Canada. https://housingrights.ca/right-to-housing-legislation-in-canada/#:~:text=The%20right%20to%20housing%20was,Economic%2C%20Social%20and%20Cultural%20Rights

- Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner OIPC (Edmonton). (2022). Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA). https://oipc.ab.ca/legislation/pipa/

- Pasalis, J. (2022). Canada’s G7-Leading Pop Growth and Housing Impact. Move Smartly. https://www.movesmartly.com/articles/canadas-g7-leading-pop-growth-and-housing-impact

- Pager, D., and Shepherd, H. (2008).The Sociology of Discrimination: Racial Discrimination in Employment, Housing, Credit, and Consumer Markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 181-209.

- Perrault, J.F. (2022). Which Province Has the Largest Structural Housing Deficit? ScotiaBank Economics Publication. https://www.scotiabank.com/ca/en/about/economics/economics-publications/post.other-publications.housing.housing-note.housing-note–january-12-2022-.html

- Springer A.(2022). Living in Colour: Racialized Housing Discrimination in Canada. Homeless Hub. https://www.homelesshub.ca/blog/living-colour-racialized-housing-Discrimination-canada

Carrie-Anne Cyre is a public health student and currently working on her master’s degree. She has been volunteering in her community for over a decade, including the UncoverOliver Working Group. When she isn’t studying or volunteering, Carrie-Anne loves travel (pre- and hopefully post-COVID), coffee, and enjoying nature.