Blog: Child Care and Municipalities

Written by Luis Murcia, ESPC Volunteer

In Alberta, child care is generally regulated by both provincial and federal governments, and rarely by the municipalities in which the facilities are located. Issues around child care often cannot be addressed by municipalities, such as long wait-lists, lack of coverage, affordability, and impacts from COVID-19. As a result, many cities struggle with ensuring access to early learning and care.” In this blog post we will explore the issue of child care coverage, some of the impacts that COVID-19 has had on the child care system, and what a few municipalities in Alberta can teach us when it comes to providing quality child care.

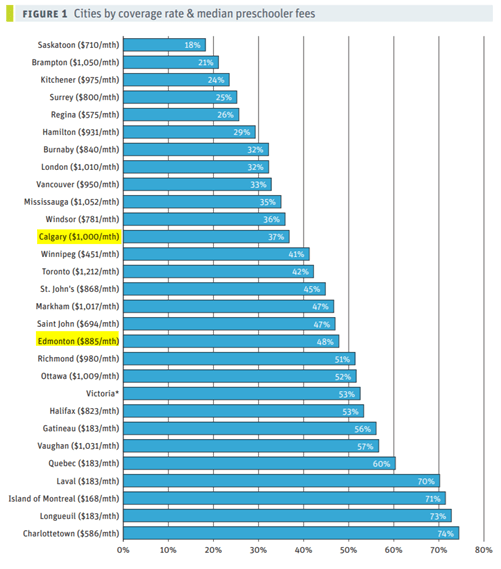

In Edmonton, as in the rest of Canada, child care can be a major struggle for parents. There are many factors that make it a challenge, including availability and affordability. In Edmonton, estimates for child care coverage range from 3 to 3.7 spaces per 10 children under four years old [1, 2]. While there has been an increase in child care coverage in past years, coverage is not evenly distributed across Edmonton [3]. In Alberta, coverage sits at just 36% for all children in the province, with Calgary and Edmonton contributing a combined coverage of 43% despite housing over half of all children in the province [4]. However, even within Edmonton, 33% of children live in a child care desert. We can see from these numbers that long wait-lists have been the norm and are not simply an outcome of the pandemic.

The child care system has been greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Though this topic deserves its own separate analysis, here are a few key facts:

- LOSS OF CHILD CARE WORKFORCE: In Alberta’s first wave, 55% of centres reported mass staff layoffs [5]. In the first year of the pandemic, Alberta lost 20% of its child care workforce—from 18,818 licensed educators in March 2020, to 14,984 in March 2021 [6].

- INCREASE IN FEES: The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) annual report shows that fees for preschool-aged children rose in several large cities in the country as a direct result of COVID-19. These increases ranged from +1% to +25%; Edmonton faced fee hikes of over 6% [6].

- DROP IN CHILD CARE ENROLLMENT: With the rise in cost there was also a decrease in enrollment rates [6]. This created a problem for facilities struggling financially throughout reopening efforts. Between February and September 2020, there was a drop of 43% in child care enrollment in Edmonton (about 10,000 spots). The CCPA report draws a strong negative correlation between declining enrollment and high fees.

At first glance, the pandemic created major challenges in child care. On closer inspection, it simply brought out the fragility of the system. COVID-19 has highlighted the feedback loop of a dwindling workforce that results in higher fees, causing parents to refrain from enrolling their children in programs [7], causing more staff to be laid off—and the cycle continues. David Macdonald, CCPA report co-author, broadly noted, “relying on exorbitant parent fees to fund services that should be part of the social infrastructure is what got us into this mess in the first place” [8].

So how can communities address child care affordability and accessibility? Fee issues will be easier to fix than availability/ accessibility. We’ve seen that when provincial and federal governments commit to subsidizing child care (such as with the $25/day or $10/day programs, discussed in a previous post on child care in Alberta), options are made available to low-income families. However, improved affordability means that wait-lists often skyrocket [9]. Making child care affordable but neglecting to address the number of licensed facilities does not actually get more children into care. Even in provinces like Quebec and P.E.I., where fees are set and capped, child care accessibility depends heavily on where parents live. Finding child care in large urban areas tends to be easier than in rural areas [4].

It’s not only a matter of making the system affordable, but also creating initiatives to increase the number of licensed early learning and child care spaces where needed [4]. If municipalities had a major role in child care, would that help deal with the ongoing issue of child care deserts? Currently in Alberta there are four municipalities that are involved in supporting child care: Jasper, Beaumont, Drayton Valley, and the Municipal District of Opportunity No. 17 (located north of Edmonton). Beaumont has a fixed budget to cover about 20% of their child care program, while the other three areas have established annual budgets to support their programs [10]. Additionally, public support in these communities has several benefits:

- Fees are lower than the provincial average for similar level of care, despite the remote locations.

- Services remain affordable for local families.

- Specific needs of the community can be targeted.

- Physical sites are developed purposefully for early learning and care.

Closer to home, the Edmonton Council for Early Learning and Care has made several recommendations in support of better early learning and child care (ELCC) [11]. To ensure child care services remain responsive to local needs and priorities, one recommendation is to support provincial system-wide planning through regional service management. When local communities have the power to plan and manage their child care services, they are better able to provide those services where needed. An example of this exists in Ontario, where 47 municipal governments are responsible for planning and managing licensed child care services at the local level [12]. They partner with schools to provide full-day kindergarten programs for all 4- to 5-year-old children. Despite being non-compulsory, most Ontarian children are enrolled in one of these programs.

Ontario’s model suggests that having municipalities involved in delivering child care is an achievable goal. Bigger cities, such as Edmonton, could benefit from getting municipalities and schools involved, as the city would have better control over accommodating local needs and vulnerable sectors, thereby making it easier to target areas at risk of child care deserts. Likewise, the four Alberta municipalities mentioned demonstrate that it is possible to provide child care in communities that are not able to support and sustain child care through a market model. Areas where child care services tend to have higher costs, such as small, isolated communities or communities with special cultural and social needs, could also benefit from having similar child care programs run by their municipality to provide better options for parents.

Municipally managed child care is not free from challenges. Currently, Albertan municipalities have no legislated obligation to play a role in funding, planning, or managing child care services. As such, any municipality that wishes to contribute to their local child care must justify expenditures for these programs during times of financial difficulty (such as the current pandemic). Provincial and federal support for regionally managed ELCC programs would go a long way towards easing that burden and providing communities with improved child care options. This is a worthwhile goal to achieve, as that support goes back to the community—for every dollar spent on child care, the general economy receives between $1.50 and $2.80 in return [13].

Other resources that may be of interest:

- https://cupe.ca/child-care-profile-alberta

- https://childcarecanada.org/taxonomy/term/7859?page=1

- https://www.ecelc.ca/publications-archive/rising-early-learning-and-care-in-calgary

About the volunteer

Luis Murcia is a volunteer with ESPC. His goal and passion is the pursuit of knowledge for the betterment of society. In 2013, he came to the University of Alberta from El Salvador and graduated with a BA in psychology and a minor in philosophy. He is striving to develop into a person that can help others become their best self.

References

- Edmonton Council for Early Learning and Care. (2020). Infographic 04, licensed full-day early learning and care spaces in Edmonton per 10 children aged 0-4. https://www.ecelc.ca/infographics/7samoydxcitxm67ems40c5f26artls

- Buschmann, R., & Partridge, E. (2019). Brief: A profile of child care in Edmonton, 2019. Edmonton Council for Early Learning and Care. https://www.ecelc.ca/publications-archive/profile-of-edmonton-child-care-in-2019

- Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. (2018). Child care deserts. https://www.policyalternatives.ca/childcaredeserts

- Macdonald, D. (2018). Child care deserts in Canada. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/child-care-deserts-canada

- Johnson, Lisa. (2021, July 16). Fragile child care sector in Alberta hit hard by COVID-19: National survey. Edmonton Journal. https://edmontonjournal.com/news/politics/fragile-child-care-sector-in-alberta-hit-hard-by-covid-19-national-survey

- Macdonald, D., & Friendly, M. (2021). Sounding the alarm: COVID-19’s impact on Canada’s precarious child care sector. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. https://www.policyalternatives.ca/TheAlarm

- Statistics Canada. (2021). Survey on early learning and child care arrangements, 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210407/dq210407b-eng.htm

- Childcare Resources and Research Unit. (2021). New report shows child care fees in Edmonton and Calgary remain high, enrolment dips due to COVID-19. https://childcarecanada.org/documents/child-care-news/21/03/new-report-shows-child-care-fees-edmonton-and-calgary-remain-high

- Childcare Resources and Research Unit. (2018). Affordable child care on the horizon for Alberta parents – but who will get in? https://childcarecanada.org/documents/child-care-news/18/04/affordable-child-care-horizon-alberta-parents-who-will-get

- The Muttart Foundation. (2011). Municipal child care in Alberta: An alternative approach to the funding and delivery of early learning and care for children and their families. https://muttart.org/reports/municipal-child-care-in-alberta-an-alternative-approach-to-the-funding-and-delivery-of-early-learning-and-care-for-children-and-their-families/

- Edmonton Council for Early Learning and Care. (2021). Recommended actions for Alberta Children’s Services in support of early learning and care. https://www.ecelc.ca/whats-new-archive/recommended-actions-for-alberta-childrens-services

- Friendly, M., Larsen, E., Feltham, L.E., Grady, B., Forer, B., & Jones, M. (2018). Early childhood education and care in Canada 2016. Childcare Resource and Research Unit. https://childcarecanada.org/publications/ecec-canada/18/04/early-childhood-education-and-care-canada-2016

- Department of Finance Canada. (2021). Budget 2021: A Canada-wide early learning and child care plan. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2021/04/budget-2021-a-canada-wide-early-learning-and-child-care-plan.html