[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.7.0″ custom_margin=”0px||0px||false|false” custom_padding=”0px||0px||false|false”][et_pb_row column_structure=”3_4,1_4″ use_custom_gutter=”on” gutter_width=”2″ _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _module_preset=”default” width=”100%” custom_margin=”0px||||false|false” custom_padding=”0px||0px||false|false” border_width_bottom=”1px” border_color_bottom=”#a6c942″][et_pb_column type=”3_4″ _builder_version=”4.7.0″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_post_title meta=”off” featured_image=”off” _builder_version=”4.7.4″ _module_preset=”default” title_font=”||||||||” custom_margin=”||3px|||” border_color_bottom=”#a6c942″][/et_pb_post_title][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_4″ _builder_version=”4.7.0″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_image src=”https://edmontonsocialplanning.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/COLOUR-BLOCKS_spaced-300×51.png” title_text=”COLOUR BLOCKS_spaced” align=”center” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _module_preset=”default” max_width=”100%” max_height=”75px” custom_margin=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”10px|0px|20px|0px|false|false” global_module=”96648″][/et_pb_image][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][et_pb_row column_structure=”3_4,1_4″ use_custom_gutter=”on” gutter_width=”2″ make_equal=”on” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” width=”100%” custom_margin=”0px|auto|0px|auto|false|false” custom_padding=”30px|0px|0px|0px|false|false”][et_pb_column type=”3_4″ _builder_version=”4.5.6″ custom_padding=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.7.5″ _dynamic_attributes=”content” _module_preset=”default” text_font=”|600|||||||” text_text_color=”#2b303a” custom_padding=”||32px|||”]@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9kYXRlIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJkYXRlX2Zvcm1hdCI6ImRlZmF1bHQiLCJjdXN0b21fZGF0ZV9mb3JtYXQiOiIifX0=@[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.7.7″ text_text_color=”#2b303a” text_line_height=”1.6em” header_2_font=”||||||||” header_2_text_color=”#008ac1″ header_2_font_size=”24px” background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” text_orientation=”justified” width=”100%” module_alignment=”left” custom_margin=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”0px||||false|false” hover_enabled=”0″ locked=”off” sticky_enabled=”0″]

Written by Jenn Rossiter and Sydney Sheloff

Racism is prevalent within our current social, political, and economic realities. Its manifestation across and between systems (for example, health care, education, criminal justice, and policing) makes it necessary to highlight specific sectors where it has caused particular harm, or been particularly influential. We’ll focus the next two posts on a couple of areas that have been in the public eye recently: policing and education. We recognize that the presence of systemic racism within these two systems is not mutually exclusive (consider School Resource Officers), and that there is a complexity in the ways that they interconnect. However, this is an attempt at a brief overview of current issues and discussions to highlight how they connect to social issues such as poverty and employment.

K-12 Schools

Edmonton has seen its share of recent media reports over incidents of racism in the K-12 school system. Take for instance the repercussions in 2019 when Emmell Summerville, at the age of 11, was asked to remove his du-rag at school due to its perceived gang affiliation. Or the Edmonton Public School Board trustee who claimed that refugee students were prone to violence (spoiler alert: they’re not).

Generally, issues in education arise from inadequate representation of BIPOC individuals as teachers or administration, and a recognition from non-BIPOC educators that they do not have the experience, tools, or resources to talk about anti-racism in the classroom. Without adequate training, and handed a highly Euro-centric curriculum, teachers are unable to effectively engage in the subject. On top of this, overt racist acts are often treated as bullying in an effort to avoid discomfort, which negatively affects identity formation and well-being among BIPOC children and youth.

In an effort to respond to calls for change in racial inequality within the education system, the Edmonton Public School Board (EPSB) has committed to the collection of race-based data—the first school board in Alberta to do so. This data will be used to address racism and racial discrimination, with the intent to measure accountability and improve equity within the school system. Board Chair Trisha Estabrooks noted that the board first needs to “understand the gaps and the inequities in order to come up with policies.” EPSB will collaborate with BIPOC communities and leaders to determine best practices in data collection. Erick Ambtman, Executive Director for EndPoverty Edmonton, and an ESPC partner agency, is quoted in the EPSB Recommendation Report, stating, “To begin to address racism and undertake effective anti-racist work, we must understand all of the ways in which racism is expressed within our systems. Race-based data collection is therefore the necessary first step in doing anti-racism work and building anti-racist policies.”

In another move, EPSB has agreed to suspend the controversial School Resource Officer (SRO) program and replace it with a Youth Enhanced Deployment model. Although this remains a collaboration with the Edmonton Police Service, according to EPSB the officers will be “trained to respond with youth. Officers will no longer be based in Edmonton Public Schools or assigned to specific schools. Officers will have community policing duties in addition to responding to calls involving youth.” Though not exactly an innovative modification, the willingness to review programs and respond to external pressures is promising. For more on the SRO program and its harms to BIPOC students and communities, you can read an article by Sydney Sheloff (ESPC Research Officer) in ESPC’s fall 2020 fACTivist newsletter.

Post-Secondary Institutions

Issues of systemic racism are not just contained to K-12 institutions. Universities are also facing their own harmful practices.

The role of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) units within universities, according to professor and expert Malinda Smith, is to “work individually and collectively to advance a shared strategic vision of a more accessible, equitable, diverse, and inclusive campus.” The University of Alberta, for example, has adopted a wide array of EDI initiatives that extend to institutional planning, research, and student supports.

However, some have argued that EDI initiatives give universities the appearance of being diverse and inclusive, without addressing the fundamental nature of racism and exclusion. For example, expecting newly hired BIPOC academics to work towards White, Western, ideals of “success;” or not addressing the policies, practices, and structures that keep them from academia in the first place.

We currently see a track record in the lack of representation in faculty, leadership, award and program committees, and large grant recipients—which ultimately places BIPOC applicants at a disadvantage. When proposals are put forward that don’t conform to Western, “tried and tested” methodologies, they are often overlooked or dismissed. This is changing, as more innovative, culturally relevant, or traditional projects are proven to succeed within the academic setting—for example, land-based learning for Indigenous studies programs, or community service-learning.

Representation also matters. If youth do not see themselves reflected in positions of leadership, as educators or administrators, they may internalize the belief that post-secondary education is unattainable. In 2016, 94% of Black youth aged 15 to 25 wanted to get a bachelor’s degree, but only 60% thought they actually could. In recent events, University of Alberta law professor Ubaka Ogbogu chose to remove his profile from the University’s website after receiving racist messages (by voicemail and email) in response to his criticism of the UCP government’s COVID-19 response. As the only Black law professor, he is aware that this move could affect prospective Black law students who will no longer see that representation within the faculty.

Why Education Matters

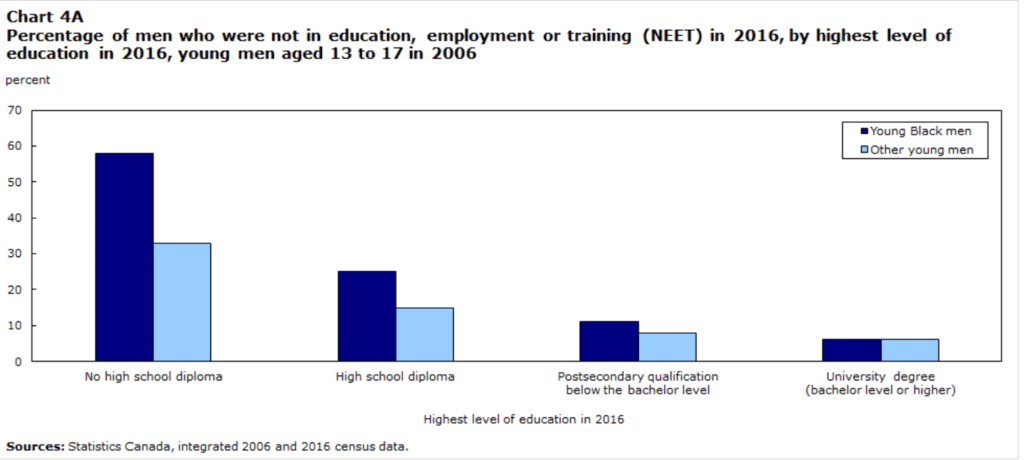

Evidence shows that employment is closely linked to education levels, especially for BIPOC communities. In 2016, the proportion of people who were not in employment, education, or training (NEET) was 58% for young Black men without a high school diploma, compared to 33% of other young men without a high school diploma. However, young Black men with a university degree had approximately the same NEET rate as other young men with a university degree (6%). In 2019, 45% of Indigenous people (aged 25–54) without a high school degree were employed, compared to 62% of the non-Indigenous population. However, for those who had completed post-secondary, 82.1% of Indigenous people were employed—nearly on par to the 87.3% of non-Indigenous people.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_4″ _builder_version=”4.7.4″ custom_padding=”0px|20px|0px|20px|false|false” border_color_left=”#a6c942″ custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_testimonial author=”Posted by:” job_title=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3IiLCJzZXR0aW5ncyI6eyJiZWZvcmUiOiIiLCJhZnRlciI6IiIsIm5hbWVfZm9ybWF0IjoiZGlzcGxheV9uYW1lIiwibGluayI6Im9uIiwibGlua19kZXN0aW5hdGlvbiI6ImF1dGhvcl93ZWJzaXRlIn19@” portrait_url=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3JfcHJvZmlsZV9waWN0dXJlIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnt9fQ==@” quote_icon=”off” portrait_width=”125px” portrait_height=”125px” disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _dynamic_attributes=”job_title,portrait_url” _module_preset=”default” body_text_color=”#000000″ author_font=”||||||||” author_text_align=”center” author_text_color=”#008ac1″ position_font=”||||||||” position_text_color=”#000000″ company_text_color=”#000000″ background_color=”#ffffff” text_orientation=”center” module_alignment=”center” custom_margin=”0px|0px|4px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”32px|0px|0px|0px|false|false”][/et_pb_testimonial][et_pb_text disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _dynamic_attributes=”content” _module_preset=”default” text_text_color=”#000000″ header_text_align=”left” header_text_color=”rgba(0,0,0,0.65)” header_font_size=”20px” text_orientation=”center” custom_margin=”||50px|||” custom_padding=”48px|||||”]@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9jYXRlZ29yaWVzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiUmVsYXRlZCBjYXRlZ29yaWVzOiAgIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6ImNhdGVnb3J5In19@[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]