The COVID-19 pandemic has had a disproportionally negative effect on Canadian women. At the start of the pandemic, women were more likely to lose jobs, and those who continued to work were more often employed in essential services that put them at a higher risk of coming into contact with the virus. The pandemic is rapidly changing our world, making it critical to keep track of changing trends.

This post will explore some of the ways this pandemic has widened a gendered division of labour. Across Canada, as industries have learned to adapt to restrictions and overall employment has improved, women continue to face inequalities, are less likely to return to work, and are more likely to take on increased child care responsibilities. In other words, as the pandemic has progressed, women have been shifting out of the labour force and back into the domestic sphere. This could have long-lasting ramifications for women’s social and economic position.

Women and Child Care

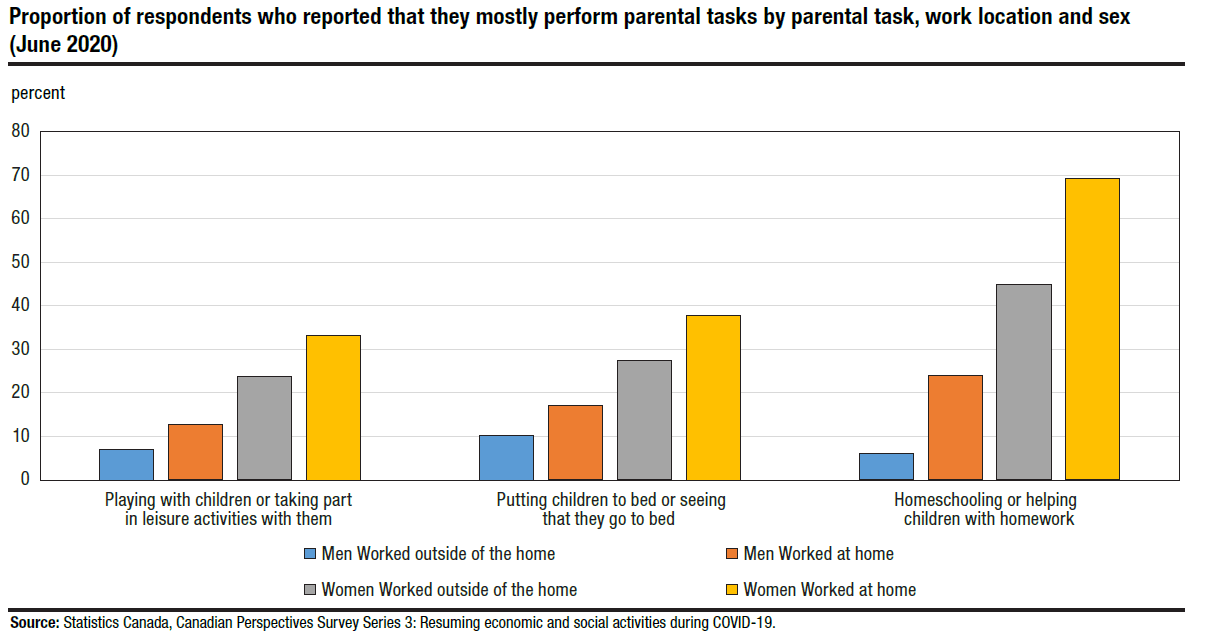

A recent study from Statistics Canada investigated how parents in couple relationships have divided child care responsibilities during the pandemic. At the start, schools and daycares were shut down to stop the spread of the virus. While these centres have since reopened, many parents are choosing to keep their children at home. Parents have therefore had to devote more time to caring for their children, and have the added responsibility of supporting them through online learning.

These increased demands have not been shared equally between parents. For example, 64% of women reported that they performed most of the homeschooling duties, and almost half (46%) of the men reported their partners did most of the homeschooling.

Child care patterns have been affected by the altered working status of parents. Men who worked at home (53%) were more likely than men who worked outside of the home (46%) to report that child care was shared equally with their partner. However, women who worked at home (40%) were more likely to report they performed most of the child care duties compared to women who worked outside the home (28%). For parents who lost their jobs due to the pandemic, men were more likely to report that parenting tasks were shared equally (56%), whereas 59% of women reported that they did the majority of the child care work.”

This study shows that men at home, whether they are unemployed or working from home, may take on more child care responsibilities, lessening the burden of women. However, women still tend to take on the majority of child care responsibilities. For women who work from home, this can be taxing on their time and contribute to high levels of stress.

Women and the Labour Force

As mentioned, women were more likely to lose their jobs at the beginning of the pandemic, but we are now seeing that they are also less likely to go back to work. A study by RBC economics found that between February and October 2020, 20,600 Canadian women left the labour force while 68,000 men joined. The number of women who have left the labour force has increased by 2.8% during the same time period.

There are three dominant reasons for this trend. First, women are more likely to be employed in industries that are slower to recover and more vulnerable to a second wave of lockdowns. Second, women may have limited opportunities to work from home compared to men. Third, as discussed, women are taking on more child care responsibilities and find it harder to work outside of the home setting.

Child care issues are closely correlated with women exiting the labour force. One of the largest cohorts of women to leave the labour force are those aged 35-39, half of whom have a child under the age of six. For all age groups, women with children under the age of six account for two thirds of those exiting the labour force. The authors suggest these women are leaving in order to focus on their increased child care responsibilities.

However, things are not all bad. Though young women aged 20-24 were another cohort that left the labour market in large numbers, three quarters were enrolled in post-secondary education. The RBC study suggests that this could mean young women are choosing to focus on school to improve their post-pandemic career prospects.

Why Does this Matter?

The authors claim that the pandemic “rolled back the clock on three decades of advances in women’s labour-force participation” (p. 1). Women are facing more domestic and child care responsibilities and reducing their participation in the paid labour market. This may have far reaching effects in terms of women’s equality. This change could place more women and children in precarious situations, and could push them into poverty.

Recovery efforts need to focus on women’s unique needs, such as providing safe and accessible child care, supporting women’s sectors in recovery efforts, supporting skill development so women can join sectors less vulnerable to the pandemic, and creating supports for women who choose to stay at home. Supporting women is imperative to a just and equitable recovery.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_4″ _builder_version=”4.7.4″ custom_padding=”0px|20px|0px|20px|false|false” border_color_left=”#a6c942″ custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_testimonial author=”Posted by:” job_title=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3IiLCJzZXR0aW5ncyI6eyJiZWZvcmUiOiIiLCJhZnRlciI6IiIsIm5hbWVfZm9ybWF0IjoiZGlzcGxheV9uYW1lIiwibGluayI6Im9uIiwibGlua19kZXN0aW5hdGlvbiI6ImF1dGhvcl93ZWJzaXRlIn19@” portrait_url=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3JfcHJvZmlsZV9waWN0dXJlIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnt9fQ==@” quote_icon=”off” portrait_width=”125px” portrait_height=”125px” disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _dynamic_attributes=”job_title,portrait_url” _module_preset=”default” body_text_color=”#000000″ author_font=”||||||||” author_text_align=”center” author_text_color=”#008ac1″ position_font=”||||||||” position_text_color=”#000000″ company_text_color=”#000000″ background_color=”#ffffff” text_orientation=”center” module_alignment=”center” custom_margin=”0px|0px|4px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”32px|0px|0px|0px|false|false”][/et_pb_testimonial][et_pb_text disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _dynamic_attributes=”content” _module_preset=”default” text_text_color=”#000000″ header_text_align=”left” header_text_color=”rgba(0,0,0,0.65)” header_font_size=”20px” text_orientation=”center” custom_margin=”||50px|||” custom_padding=”48px|||||”]@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9jYXRlZ29yaWVzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiUmVsYXRlZCBjYXRlZ29yaWVzOiAgIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6ImNhdGVnb3J5In19@[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]