[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.7.0″ custom_margin=”0px||0px||false|false” custom_padding=”0px||0px||false|false”][et_pb_row column_structure=”3_4,1_4″ use_custom_gutter=”on” gutter_width=”2″ _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _module_preset=”default” width=”100%” custom_margin=”0px||||false|false” custom_padding=”0px||0px||false|false” border_width_bottom=”1px” border_color_bottom=”#a6c942″][et_pb_column type=”3_4″ _builder_version=”4.7.0″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_post_title meta=”off” featured_image=”off” _builder_version=”4.7.4″ _module_preset=”default” title_font=”||||||||” custom_margin=”||3px|||” border_color_bottom=”#a6c942″][/et_pb_post_title][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_4″ _builder_version=”4.7.0″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_image src=”https://edmontonsocialplanning.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/COLOUR-BLOCKS_spaced-300×51.png” title_text=”COLOUR BLOCKS_spaced” align=”center” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _module_preset=”default” max_width=”100%” max_height=”75px” custom_margin=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”10px|0px|20px|0px|false|false” global_module=”96648″][/et_pb_image][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][et_pb_row column_structure=”3_4,1_4″ use_custom_gutter=”on” gutter_width=”2″ make_equal=”on” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” width=”100%” custom_margin=”0px|auto|0px|auto|false|false” custom_padding=”30px|0px|0px|0px|false|false”][et_pb_column type=”3_4″ _builder_version=”4.5.6″ custom_padding=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.7.5″ _dynamic_attributes=”content” _module_preset=”default” text_font=”|600|||||||” text_text_color=”#2b303a” custom_padding=”||32px|||”]@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9kYXRlIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJkYXRlX2Zvcm1hdCI6ImRlZmF1bHQiLCJjdXN0b21fZGF0ZV9mb3JtYXQiOiIifX0=@[/et_pb_text][et_pb_button button_url=”https://edmontonsocialplanning.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Race-Based-Data_ESPCFeatureReport_Feb2021.pdf” button_text=”Download Confronting Racism with Data: Why Canada Needs Disaggregated Race-Based Data (PDF)” _builder_version=”4.9.0″ _module_preset=”default” custom_button=”on” button_text_color=”#ffffff” button_bg_color=”#008ac1″ custom_margin=”||19px|||” custom_padding=”||5px|||”][/et_pb_button][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.9.0″ text_text_color=”#2b303a” text_line_height=”1.6em” header_2_font=”||||||||” header_2_text_color=”#008ac1″ header_2_font_size=”24px” background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” text_orientation=”justified” width=”100%” module_alignment=”left” custom_margin=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”25px||||false|false” locked=”off”]

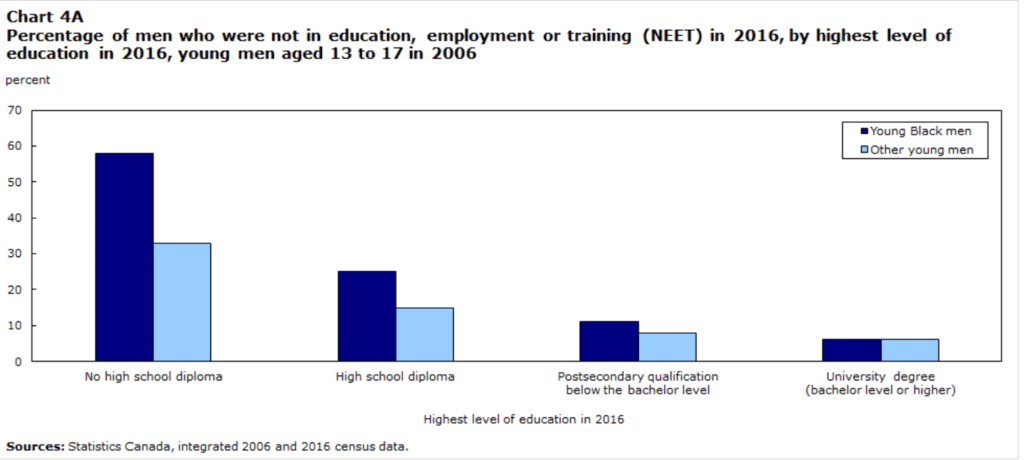

History has shown that race-based data can be used to uphold racist systems and discriminatory practices; but data can also help to dismantle them. Currently, race-based data is collected in only a few key systems, and data collection strategies are woefully inadequate for current needs (in areas such as health, justice, and education). The limited data that is available does not provide adequate evidence to support targeted policy change and intervention. Race-based data is crucial to develop effective anti-racism frameworks, and to understand the diverse, intersectional, needs of racialized communities in Canada. This report highlights some of the issues, and addresses how systems can improve, or implement, data collection strategies that result in reliable, high-quality, and comparable data—based firmly on national-level standards.

Authors:

Jenn Rossiter, Research Services and Capacity Building Coordinator

Tom Ndekezi, volunteer and ESPC Canada Summer Jobs student (2020)

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_4″ _builder_version=”4.7.4″ custom_padding=”0px|20px|0px|20px|false|false” border_color_left=”#a6c942″ custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_testimonial author=”Posted by:” job_title=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3IiLCJzZXR0aW5ncyI6eyJiZWZvcmUiOiIiLCJhZnRlciI6IiIsIm5hbWVfZm9ybWF0IjoiZGlzcGxheV9uYW1lIiwibGluayI6Im9uIiwibGlua19kZXN0aW5hdGlvbiI6ImF1dGhvcl93ZWJzaXRlIn19@” portrait_url=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3JfcHJvZmlsZV9waWN0dXJlIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnt9fQ==@” quote_icon=”off” portrait_width=”125px” portrait_height=”125px” disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _dynamic_attributes=”job_title,portrait_url” _module_preset=”default” body_text_color=”#000000″ author_font=”||||||||” author_text_align=”center” author_text_color=”#008ac1″ position_font=”||||||||” position_text_color=”#000000″ company_text_color=”#000000″ background_color=”#ffffff” text_orientation=”center” module_alignment=”center” custom_margin=”0px|0px|4px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”32px|0px|0px|0px|false|false”][/et_pb_testimonial][et_pb_text disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _dynamic_attributes=”content” _module_preset=”default” text_text_color=”#000000″ header_text_align=”left” header_text_color=”rgba(0,0,0,0.65)” header_font_size=”20px” text_orientation=”center” custom_margin=”||50px|||” custom_padding=”48px|||||”]@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9jYXRlZ29yaWVzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiUmVsYXRlZCBjYXRlZ29yaWVzOiAgIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6ImNhdGVnb3J5In19@[/et_pb_text][et_pb_code _builder_version=”4.9.7″ _module_preset=”default” text_orientation=”center” hover_enabled=”0″ sticky_enabled=”0″][3d-flip-book mode=”thumbnail-lightbox” id=”142869″ title=”true”][/3d-flip-book]

Click on image to view online.

[/et_pb_code][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]