[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.19.2″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][/et_pb_section][et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.16″ custom_margin=”0px||0px||false|false” custom_padding=”0px||0px||false|false” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_row column_structure=”3_4,1_4″ use_custom_gutter=”on” _builder_version=”4.16″ _module_preset=”default” width=”100%” custom_margin=”0px||||false|false” custom_padding=”0px||0px||false|false” border_width_bottom=”1px” border_color_bottom=”#a6c942″ global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_column type=”3_4″ _builder_version=”4.16″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_post_title meta=”off” featured_image=”off” _builder_version=”4.16″ _module_preset=”default” title_font=”||||||||” custom_margin=”||3px|||” border_color_bottom=”#a6c942″ global_colors_info=”{}”][/et_pb_post_title][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_4″ _builder_version=”4.16″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_image src=”https://edmontonsocialplanning.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/COLOUR-BLOCKS_spaced-300×51.png” title_text=”COLOUR BLOCKS_spaced” align=”center” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _module_preset=”default” max_width=”100%” max_height=”75px” custom_margin=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”10px|0px|20px|0px|false|false” global_module=”96648″ global_colors_info=”{}”][/et_pb_image][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][et_pb_row column_structure=”3_4,1_4″ use_custom_gutter=”on” make_equal=”on” _builder_version=”4.16″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” width=”100%” custom_margin=”0px|auto|0px|auto|false|false” custom_padding=”30px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_column type=”3_4″ _builder_version=”4.16″ custom_padding=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” global_colors_info=”{}” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.16″ _dynamic_attributes=”content” _module_preset=”default” text_font=”|600|||||||” text_text_color=”#2b303a” custom_padding=”||32px|||” global_colors_info=”{}”]@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9kYXRlIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJkYXRlX2Zvcm1hdCI6ImRlZmF1bHQiLCJjdXN0b21fZGF0ZV9mb3JtYXQiOiIifX0=@[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.23.1″ text_text_color=”#2b303a” text_line_height=”1.6em” header_2_font=”||||||||” header_2_text_color=”#008ac1″ header_2_font_size=”24px” background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” text_orientation=”justified” width=”100%” module_alignment=”left” custom_margin=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”25px||||false|false” hover_enabled=”0″ locked=”off” global_colors_info=”{}” sticky_enabled=”0″]

Written by Janell Uden, Research Services and Capacity Building Coordinator

There is a lot of controversy surrounding a recent bill passed in Saskatchewan, which requires that schools obtain parental consent before a child under sixteen years old can use a preferred name, pronoun or gender expression at school. One take that has been building momentum during this new wave movement of prioritizing “parental rights” in education- are those who feel that parents need to protect their children from the indoctrination of the government in schools. Those opposing this parental rights bill say that schools should be protecting 2SLGBTQ+ youth from the negative risk factors they could face if they do not live in a supportive home. The priority of the debate gets lost when both sides argue, as both children’s families and schools should be safe, supportive, and protective places. It draws away attention from the children, who are the subject of concern.

To further explain, some are worried that allowing children to change their gender, name, or pronouns at school without parental consent is violating the parental right to know what is going on with their child, especially something as important as this. Some of these parents want to be informed and be the ones to educate their child on this subject. This could be concerning, if some of these parents want to teach their children that their identity is wrong. Other parents know that not all 2SLGBTQ+ youth have parents who are accepting of their child’s gender expression, sexual orientation, or gender identity and when this is the case, youth’s lives are negatively altered. As a result of the seriousness of these potential risks, some parents don’t think they’re worth taking, and the disclosure of this information should be left up to the youth. This law prioritizes “parental rights” to know what is going on with their child, when that child is trying to explore their gender and sexuality. Rather than creating a safe and comfortable environment for their children to talk to them, one might wonder if this failing of familial communication is a priority for this government? In situations where parents don’t know their child’s gender, pronoun, name change in school it is likely because the child either hasn’t told their parents yet because they are not ready, or they may be scared to do so.

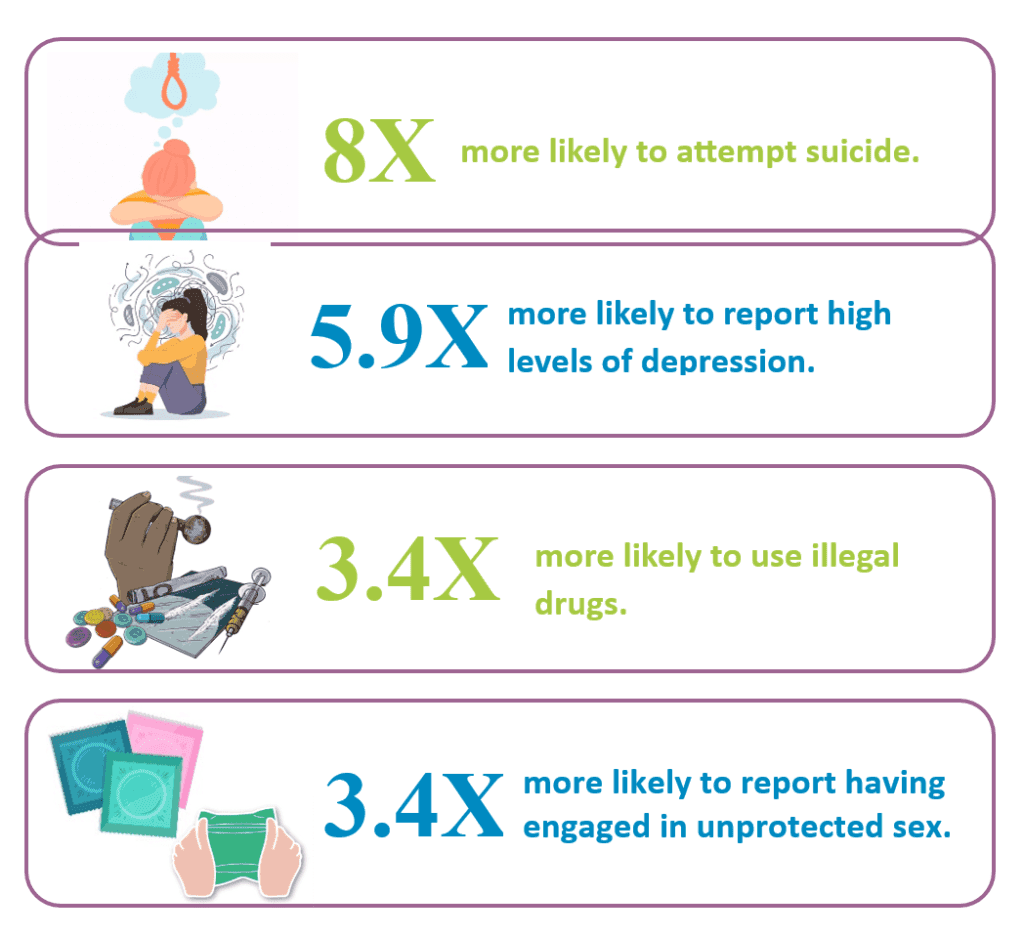

As mentioned, 2SLGBTQ+ youth who do not live in supportive homes face increased risks.

|

One of these risks is youth homelessness. Past research shows that up to 40% of young people who experience homelessness are 2SLGBTQ+, (Abramovich & Shelton, 2017). Meanwhile, 2SLGBTQ+ youth only make up as estimated 5-10% of housed youth (Abramovich & Shelton, 2017). |

Compared to 2SLGBTQ+ youth who receive familial support, those whose families reject them are (Côté & Blais, 202; Ryan et al., 2009):

The greatest predictor of future involvement with the juvenile justice system for 2SLGBTQ+ youth is having to leave home because of family rejection (Fedders, 2006). Being without basic needs such as housing and food, these youth are forced to commit “survival crimes” or to leave school so they can earn an income (Majd et al., 2006). While we all can agree that parents should know what is going on in their child’s life, keeping the facts above in mind, it raises the question of is it worth placing child’s rights, below “parental rights”?

To pass this law in Saskatchewan, the premier has had to invoke the notwithstanding clause to override the children’s chart rights and rush the passing of this bill, instead of taking it through the normal legislative process (Hunter, 2023). The notwithstanding clause can override certain sections of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Saskatchewan Human Rights Code (Hunter, 2023). Is it just for a law to have to use this clause to violate both provincial and federal human rights codes, as well as Canada’s agreement to the United Nation’s Convention on Rights to the Child to prioritize parent’s rights over their children’s rights? Saskatchewan and New Brunswick may be the minority in trying to push these bills as far as all the provinces go, however Alberta may not be far behind.

This weekend at the United Conservative Party Annual General Meeting, there was an overwhelming majority of support for a resolution that proposes the same school pronoun bill as Saskatchewan (Johnson, 2023). This attendance of this weekend’s UCP AGM set a record for the largest provincial party meeting in Alberta’s history (Kury de Castillo, 2023). The Premier also made a clear statement in her address supporting parental rights and choices in education, while condemning the far left for ‘undermining’ the role of parents.

When this bill was brought up in Saskatchewan, the government took nine days to draft its pronoun policy and released it to the public four days later (Simes, 2023). School boards were not consulted, and 2SLGBTQ+ youth certainly were not consulted. As discussions of this happening in other provinces and a resolution vote happening at a political party’s AGM are not surefire signs that this will happen here, there is certainly already discussion. Even the rumblings of this bill passing in other provinces will lead to household discussions where 2SLGBTQ+ youth find out if their house is a safe place for them or not.

In 2014, an MLA tried to pass a bill that would require that students get permission to join a Gay Straight Alliance Group at school (GSA) at school. This bill was shut down due to a lot of public pushback, and we here at ESPC had a role in hosting public consultations surrounding this bill. This suggests that with proper advocacy and public education, the gender, pronoun and name bill could meet the same fate. Currently, students in Alberta do not have to obtain parental permission to participate in a GSA group at school due to concerns of the potential of familial discrimination and lack of support (Alberta Teachers Association, 2018). The Alberta Teachers Association also states that unwanted breaches of sexual orientation and gender identity to a parent without the express consent of the student can have potentially devastating and life-threatening consequences (Alberta Teachers Association, 2018). If this is the agreed upon best practice for teachers and schools navigating youth’s involvement in GSA’s, why would the reasoning differ for pronoun, name or gender changes? Hopefully the Alberta school board will be consulted if this policy proposal moves any further past this AGM, and although the youth likely won’t be consulted due to the nature of the bill, perhaps the rest of us can centre the youth’s needs as this conversation is just beginning.

References

Abramovich, A., & Shelton, J. (Eds.). (2017). Where Am I Going to Go? Intersectional Approaches to Ending LGBTQ2S Youth Homelessness in Canada & the U.S. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press.

Alberta Teachers’ Association. (2018, August). GSAs and QSAs in Alberta Schools – A Guide for Teachers. The Alberta Teachers Association. https://legacy.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/Publications/Human-Rights-Issues/PD-80-6%20GSA-QSA%20Guide%202018.pdf

Côté, P.-B., & Blais, M. (2020). “the least loved, that’s what I was”: A qualitative analysis of the pathways to homelessness by lgbtq+youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 33(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2020.1850388

Fedders, Barbara (2006) “Coming Out for Kids: Recognizing, Respecting, and Representing LGBTQ Youth,” Nevada Law Journal: Vol. 6: Iss. 3, Article 15.

Available at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/nlj/vol6/iss3/15

Hunter, A. (2023, October 14). Sask. government use of notwithstanding clause, school policy could overshadow fall legislative sitting. CBC News. Retrieved November 6, 2023, from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/sask-notwithstanding-clause-1.6995293.

Johnson, L. (2023, November 4). Alberta UCP members approve party policy pushing for parental consent on pronouns. Edmonton Journal. Retrieved November 5, 2023, from https://edmontonjournal.com/news/politics/nine-months-on-still-no-alberta-sovereignty-act-inspired-suit-from-onion-lake-cree-nation

Kury de Castillo, C. (2023, November 5). Alberta’s UCP AGM givces party a ‘sense of direction’: expert. Global News. Retrieved November 6, 2023, from https://globalnews.ca/news/10072206/alberta-ucp-agm-sense-of-direction/

Majd, K., Marksamer, J., Reyes, C. (2009). Hidden Injustice: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Juvenille Courts. Legal Services for Chilren, National Juvenille Defender Center, and National Center for Lesbian Rights. https://www.modelsforchange.net/publications/237/Hidden_Injustice_Lesbian_Gay_Bisexual_and_Transgender_Youth_in_Juvenile_Courts.pdf

Ryan, C., Huebner, D., Diaz, R. M., & Sanchez, J. (2009). Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino Lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics, 123(1), 346–352. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3524

Simes, J. (2023, October 18). Saskatchewan’s pronoun and naming changes at school part of larger trend: professor. The Canadian Press. Retrieved November 6, 2023, from https://www.thecanadianpressnews.ca/politics/saskatchewans-pronoun-and-naming-changes-at-school-part-of-larger-trend-professor/article_232094bd-5a46-5f3b-9e2a-976fbdb2644e.html

[/et_pb_text][dmpro_button_grid _builder_version=”4.18.0″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][/dmpro_button_grid][dmpro_image_hotspot _builder_version=”4.17.4″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][/dmpro_image_hotspot][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_4″ _builder_version=”4.16″ custom_padding=”0px|20px|0px|20px|false|false” border_color_left=”#a6c942″ global_colors_info=”{}” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_testimonial author=”Posted by:” job_title=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3IiLCJzZXR0aW5ncyI6eyJiZWZvcmUiOiIiLCJhZnRlciI6IiIsIm5hbWVfZm9ybWF0IjoiZGlzcGxheV9uYW1lIiwibGluayI6Im9uIiwibGlua19kZXN0aW5hdGlvbiI6ImF1dGhvcl93ZWJzaXRlIn19@” portrait_url=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3JfcHJvZmlsZV9waWN0dXJlIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnt9fQ==@” quote_icon=”off” portrait_width=”125px” portrait_height=”125px” disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.16″ _dynamic_attributes=”job_title,portrait_url” _module_preset=”default” body_text_color=”#000000″ author_font=”||||||||” author_text_align=”center” author_text_color=”#008ac1″ position_font=”||||||||” position_text_color=”#000000″ company_text_color=”#000000″ background_color=”#ffffff” text_orientation=”center” module_alignment=”center” custom_margin=”0px|0px|4px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”32px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” global_colors_info=”{}”][/et_pb_testimonial][et_pb_text disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.16″ _dynamic_attributes=”content” _module_preset=”default” text_text_color=”#000000″ header_text_align=”left” header_text_color=”rgba(0,0,0,0.65)” header_font_size=”20px” text_orientation=”center” custom_margin=”||50px|||” custom_padding=”48px|||||” global_colors_info=”{}”]@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9jYXRlZ29yaWVzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiUmVsYXRlZCBjYXRlZ29yaWVzOiAgIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6ImNhdGVnb3J5In19@[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]