Introduction

The right to vote in elections is considered one of the most important components of a democracy. Today, any Canadian citizen 18 years of age or older is eligible to cast their ballot in a municipal, provincial, and federal election. Unfortunately, this hasn’t always been the case. Voting was originally permitted only for men affluent enough to own land or pay taxes. Those who did not meet this criteria—based on lack of property ownership or because of their gender, race, or religion—were excluded. White women were granted the right to vote by 1918 and in 1920 property qualifications were abolished. Between the end of the Second World War and up to the early 1960s, disqualification on racial and religious grounds were eliminated, culminating when all First Nations peoples were granted the unconditional right to vote in 1960 without losing their status. By 1970, the voting age was lowered from 21 years of age to 18.

The evolution of voting rights and the ways in which people have historically been included—or excluded—is an important reminder that voting is not something to be taken for granted. In 2021, Edmontonians have the chance to vote in both a municipal and federal election (October 18 and September 20, respectively). With the chance to vote for a mayor, city councillor, school board trustee, and member of Parliament, we as citizens have a big responsibility to demonstrate which direction we want our city and our country to go.

What Are Organizations Doing to Engage Voters and Increase Voter Turnout?

A number of groups and initiatives do outreach work to engage voters, especially those who may not turn out in large numbers to the voting booth. Some notable initiatives with a focus on the federal election include the following:

Apathy is Boring is a national charitable organization that educates and supports youth to become active and contributing citizens to Canada’s democracy. In addition to mobilizing voter turnout, the group works toward empowering youth to meaningfully engage with all aspects of the democratic process.

Vote Housing is a national, non-partisan, grassroots advocacy campaign led by a coalition of advocates for affordable housing and the elimination of homelessness. It seeks to engage voters on issues of housing and to cast votes based on political party and candidate plans to address these issues.

The Canadian Alliance of Student Associations launched a nationwide Get Out the Vote campaign together with 24 student associations (including the University of Alberta, MacEwan University, and Athabasca University). The campaign seeks to engage with students on the importance of voting and how it can shape their future.

The On Canada Project is a grassroots initiative focused on mobilizing youth (millennials and Generation Z) to build a community of change agents to disrupt the status quo. Originally launched to share credible information about the COVID-19 pandemic targeted to youth and marginalized populations, its mandate broadened to focus on giving younger Canadians the information they need to compassionately disrupt the status quo. This has included sharing information on voting, challenging apathy, and analyzing debates.

Voter Turnout in Previous Elections

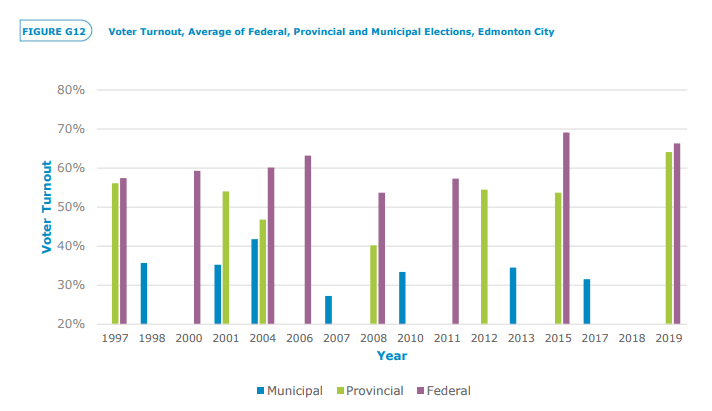

The right to vote is only effective when citizens exercise this right and show up to cast their ballot. The chart below represents voter turnout among Edmontonians in every municipal, provincial, and federal election between 1997 and 2019. Though voter turnout does fluctuate with each election cycle, the overall trend is that voter turnout is highest for federal elections (the highest was 69.1% in 2015) and lowest for municipal elections (the lowest was 27.2% in 2007). Competitive races in general—those with the prospect of a change in provincial or federal government or a competitive mayoral race—tend to lead to higher voter turnout.

Figure 1— Source: Tracking the Trends, 2020

It is clear that more work needs to be done to increase voter turnout and facilitate voter engagement, especially at the municipal level. While provincial and federal governments tackle big and sweeping issues, municipalities engage with citizens on a local level. This is crucial to building and maintaining vibrant communities that are responsive to neighbourhood concerns. Decisions that elected officials make at all levels of government affect all of our lives, both directly and indirectly. They especially impact those coming from marginalized or underserved groups—whether they are racialized or Indigenous, women, LGBTQ2S+, seniors, immigrants and refugees, children and youth, persons with disabilities, or others. Maximizing voter turnout among the eligible population is crucial to a healthy democracy.

Voting Options for the Federal and Municipal Elections

Federal Election

Canada’s federal election will be held on September 20, 2021. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Elections Canada is anticipating more interest in voting by mail. The deadline for this option has passed; registration for those wishing to exercise this option ended on September 14.

Advance polls were available on September 10, 11, 12, and 13. Locations for designated election day polls can be found through Elections Canada’s Voter Information Service. Close to 5.8 million Canadians have already voted in advance, which is a record turnout for advance voting.

Whether voters cast their ballot by mail, in an advance poll, or on election day, it is important that they are registered to vote. This can be done in advance through the Elections Canada website, in-person at any Elections Canada office, or at the polling station on voting day.

In previous elections, advance polling stations were set up at post-secondary institutions specifically for students to cast their ballot for any riding in Canada. This was part of an initiative called Vote on Campus, which was credited for increasing voter turnout. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this initiative is not being offered for the 2021 election. Advocates say this will place barriers on students’ ability to vote.

Municipal Election

Edmonton’s municipal election will be held on October 18, 2021. Advance voting will be offered from October 4 to 13. Voting locations for advance voting or election day voting can be found using the City of Edmonton’s Find Your Voting Station online tool. The number of advance voting stations has doubled from the previous election and there will be a total of 212 voting stations available across the city on election day.

Those who cannot vote on election day or at an advance voting station due to a disability or absence from the city can request a special ballot through the City of Edmonton Elections office.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_4″ _builder_version=”4.7.4″ custom_padding=”0px|20px|0px|20px|false|false” border_color_left=”#a6c942″ global_colors_info=”{}” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_testimonial author=”Posted by:” job_title=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3IiLCJzZXR0aW5ncyI6eyJiZWZvcmUiOiIiLCJhZnRlciI6IiIsIm5hbWVfZm9ybWF0IjoiZGlzcGxheV9uYW1lIiwibGluayI6Im9uIiwibGlua19kZXN0aW5hdGlvbiI6ImF1dGhvcl93ZWJzaXRlIn19@” portrait_url=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3JfcHJvZmlsZV9waWN0dXJlIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnt9fQ==@” quote_icon=”off” portrait_width=”125px” portrait_height=”125px” disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _dynamic_attributes=”job_title,portrait_url” _module_preset=”default” body_text_color=”#000000″ author_font=”||||||||” author_text_align=”center” author_text_color=”#008ac1″ position_font=”||||||||” position_text_color=”#000000″ company_text_color=”#000000″ background_color=”#ffffff” text_orientation=”center” module_alignment=”center” custom_margin=”0px|0px|4px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”32px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” global_colors_info=”{}”][/et_pb_testimonial][et_pb_text disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _dynamic_attributes=”content” _module_preset=”default” text_text_color=”#000000″ header_text_align=”left” header_text_color=”rgba(0,0,0,0.65)” header_font_size=”20px” text_orientation=”center” custom_margin=”||50px|||” custom_padding=”48px|||||” global_colors_info=”{}”]@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9jYXRlZ29yaWVzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiUmVsYXRlZCBjYXRlZ29yaWVzOiAgIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6ImNhdGVnb3J5In19@[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]