[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.7.0″ custom_margin=”0px||0px||false|false” custom_padding=”0px||0px||false|false”][et_pb_row column_structure=”3_4,1_4″ use_custom_gutter=”on” gutter_width=”2″ _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _module_preset=”default” width=”100%” custom_margin=”0px||||false|false” custom_padding=”0px||0px||false|false” border_width_bottom=”1px” border_color_bottom=”#a6c942″][et_pb_column type=”3_4″ _builder_version=”4.7.0″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_post_title meta=”off” featured_image=”off” _builder_version=”4.7.4″ _module_preset=”default” title_font=”||||||||” custom_margin=”||3px|||” border_color_bottom=”#a6c942″][/et_pb_post_title][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_4″ _builder_version=”4.7.0″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_image src=”https://edmontonsocialplanning.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/COLOUR-BLOCKS_spaced-300×51.png” title_text=”COLOUR BLOCKS_spaced” align=”center” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _module_preset=”default” max_width=”100%” max_height=”75px” custom_margin=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”10px|0px|20px|0px|false|false” global_module=”96648″][/et_pb_image][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][et_pb_row column_structure=”3_4,1_4″ use_custom_gutter=”on” gutter_width=”2″ make_equal=”on” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” width=”100%” custom_margin=”0px|auto|0px|auto|false|false” custom_padding=”30px|0px|0px|0px|false|false”][et_pb_column type=”3_4″ _builder_version=”4.5.6″ custom_padding=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.7.5″ _dynamic_attributes=”content” _module_preset=”default” text_font=”|600|||||||” text_text_color=”#2b303a” custom_padding=”||32px|||”]@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9kYXRlIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJkYXRlX2Zvcm1hdCI6ImRlZmF1bHQiLCJjdXN0b21fZGF0ZV9mb3JtYXQiOiIifX0=@[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.9.4″ text_text_color=”#2b303a” text_line_height=”1.6em” header_2_font=”||||||||” header_2_text_color=”#008ac1″ header_2_font_size=”24px” background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” text_orientation=”justified” width=”100%” module_alignment=”left” custom_margin=”0px|0px|0px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”25px||||false|false” hover_enabled=”0″ locked=”off” sticky_enabled=”0″]

Written by Jayme Wong, ESPC Volunteer

In August 2020, the busiest supervised consumption site in North America closed just two years after it opened its doors in Lethbridge, Alberta. The location, which saw a total of 444,781 visitors between January 2018 and June 2020, [1] was shut down following the release of a controversial provincial report that expressed “inadequate oversight and the lack of accountability mechanisms” [2] at supervised consumption services sites in Alberta (among other factors [3]) as reasons for the suspension of provincial funding. Now, a year after the widely debated decision, Albertans are still waiting to hear about next steps.

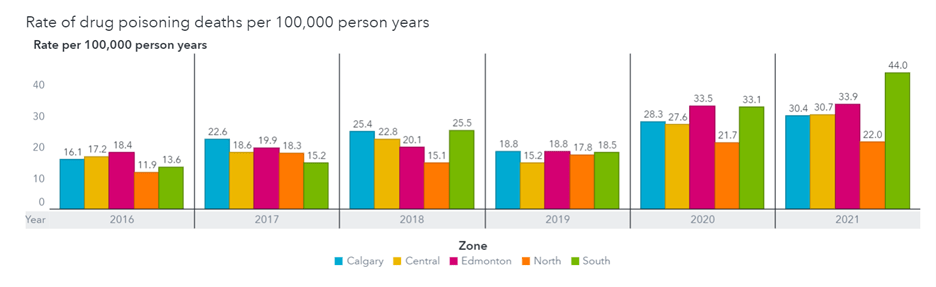

According to Alberta Health Services, “supervised consumption services are part of a range of evidence-based services that support prevention, harm reduction and treatment for Albertans living with substance use challenges.” [4] In addition to providing a safe, clean space for people to use drugs, supervised consumption sites also provide counselling and addictions support to visitors. Evidence collected across the province from the second quarter of 2020 [1] suggests that the services provided by supervised consumption sites are needed—the South Zone had the highest rate of fentanyl deaths at 23.1 per 100,000 person years; the Edmonton Zone followed closely with 19.9 per 100,000 person years. (see: Note 1)

Despite numerous public health experts opposing the closure of these sites, [5] supervised consumption services have been the target of harsh criticisms from the general public. Increases in panhandling, loitering, shoplifting and discarded drug paraphernalia have all been cited as reasons to oppose sites. [6] Small business owners and homeowners claim that they have been negatively affected by supervised consumption sites. These concerns were only confirmed and amplified when the Government of Alberta released its controversial socio-economic review of supervised consumption sites in March 2020. [2] The report highlighted concerns in eight general categories:

- public safety

- general social disorder

- consultation/communication issues

- appropriateness of current response

- concerns with access to treatment

- homelessness

- economic impacts on property and business

- site operation

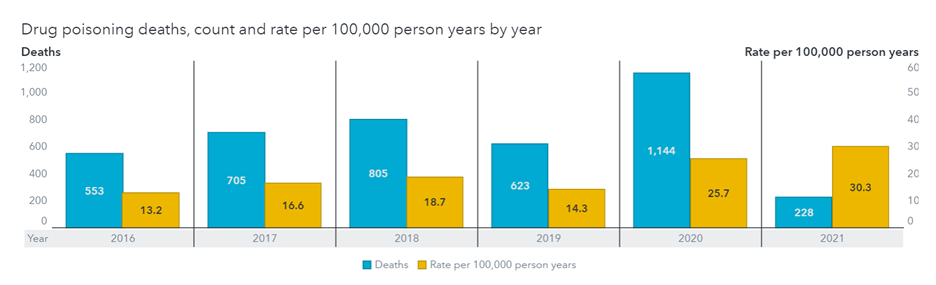

Critics claimed that the government report used extremely biased language and capitalized on people’s existing fears. Nonetheless, the report was effective in sparking a conversation about the best way to handle drug addiction. The government report states that there has been too much emphasis on harm reduction, though little has been done to address the remaining three pillars of the national drugs and substances strategy: prevention, enforcement, and treatment. [7] The lack of movement has been frustrating to say the least. In 2020, 1,144 Albertans died of opioid-related causes [8]; the rates spiked during peak COVID-19 quarantine months in May, June, and July. This number is alarming compared to the 623 total deaths that occurred in the entirety of 2019.

Currently, Alberta Health Services offers supervised consumption services through a mobile unit in Lethbridge. [9] However, the closure of the brick-and-mortar site has not decreased the number of people who require services. The single mobile unit has been unable to meet the demands of the thousands of displaced people who previously relied on the now-closed supervised consumption site. This has prompted citizens like Tim Slaney to open an unsanctioned nightly pop-up overdose prevention site in the city’s urban centre. [10] The site has had to continually move locations and operate under the radar to avoid fines. In other words, the closing of the Lethbridge site did not alleviate the fentanyl problem, nor did it resolve the concerns of downtown business owners. It only forced people to operate in more challenging conditions.

This is the reality that we are currently in: “On average, in the first six months of 2020, 2.5 individuals died every day in Alberta as a result of an unintentional opioid poisoning.” [1] Addiction is a silent killer that affects the province in ways that numbers and statistics can never illustrate. The problem affects all Albertans—including our neighbours, co-workers, and friends. It affects people like Jacob Bulloch, who was only 19 years old when he died of a fentanyl overdose last November. [11] He struggled with mental health issues and used drugs as a coping mechanism. His mother, Cheryl, believes that if there were more supports and resources for people struggling with addictions then her son’s battle may not have been so stigmatized, and his story may have ended differently.

The supervised consumption sites debate continues, but the issue expands beyond policy and property. The problem is deeply rooted in societal perceptions of mental health and who is deemed “worthy” of saving. The myths and misconceptions surrounding addictions are prohibiting our ability to prevent avoidable deaths. While we all wait for the government’s next steps, perhaps it is time for Albertans to expand our worldview and see the biases that were there all along. (see Note 2)

Note 1: person years refer to the number of persons who participate in a study for a specific timeframe—in this case, 100,000 people over one year.

Note 2: Since the writing of this post, it was announced that Edmonton’s own Boyle Street safe consumption site would be permanently closed at the end of April, 2021.

About the author: Jayme Wong is an ESPC volunteer. She graduated from the University of Lethbridge in 2014 with a BA in English and Philosophy, and more recently graduated from the University of Alberta in 2020 with an MA in English and Film Studies. She currently works at a local non-profit, the Learning Centre Literacy Association.

References and Links

[1] Government of Alberta. (2020). COVID-19 Opioid response surveillance report, Q2 2020. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/f4b74c38-88cb-41ed-aa6f-32db93c7c391/resource/e8c44bab-900a-4af4-905a-8b3ef84ebe5f/download/health-alberta-covid-19-opioid-response-surveillance-report-2020-q2.pdf

[2] Government of Alberta. (2020). Impact: A socio-economic review of supervised consumption sites in Alberta. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/dfd35cf7-9955-4d6b-a9c6-60d353ea87c3/resource/11815009-5243-4fe4-8884-11ffa1123631/download/health-socio-economic-review-supervised-consumption-sites.pdf

[3] Government of Alberta. (2020). Grant expenditure review for Alberta Health. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/90fb3c93-79e7-481b-8e1f-3dbe122f4f27/resource/ec2eead9-1c42-4f72-8d88-4199daec44e5/download/health-grant-expenditure-review-arches-2020-07.pdf

[4] Alberta Health Services. (n.d.) Supervised consumption services. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/info/Page15434.aspx

[5] Smith, A. (2020, June). U of C study finds supervised consumption sites could save Alberta government money. Calgary Herald. https://calgaryherald.com/news/u-of-c-study-finds-supervised-consumption-sites-could-save-alberta-government-money

[6] Labby, B. (2020, August). Lethbridge braces for closure of Canada’s busiest supervised consumption site. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/lethbridge-arches-supervised-consumption-site-closure-1.4434070

[7] Government of Canada. (2016, December). Pillars of the Canadian drugs and substances strategy. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/healthy-living/pillars-canadian-drugs-substances-strategy.html

[8] Government of Alberta. (2021). Substance use surveillance data. https://healthanalytics.alberta.ca/SASVisualAnalytics/?reportUri=%2Freports%2Freports%2F1bbb695d-14b1-4346-b66e-d401a40f53e6§ionIndex=0&sso_guest=true&reportViewOnly=true&reportContextBar=false&sas-welcome=false

[9] French, J. (2020, July). Mobile supervised consumption site inadequate to meet Lethbridge’s needs, critics say. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/mobile-supervised-consumption-site-inadequate-to-meet-lethbridge-s-needs-critics-say-1.5653154

[10] Nagy, M., & Neustaeter, B. (2020, October). Alberta city struggling with surge in opioid deaths as advocates call for more safe injection sites. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/alberta-city-struggling-with-surge-in-opioid-deaths-as-advocates-call-for-more-safe-injection-sites-1.5132391

[11] Strasser, S. (2021, April). Airdrie resident speaks up about mental health importance following son’s overdose death. St. Albert Today. https://www.stalberttoday.ca/beyond-local/airdrie-resident-speaks-up-about-mental-health-importance-following-sons-overdose-death-3613953

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_4″ _builder_version=”4.7.4″ custom_padding=”0px|20px|0px|20px|false|false” border_color_left=”#a6c942″ custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_testimonial author=”Posted by:” job_title=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3IiLCJzZXR0aW5ncyI6eyJiZWZvcmUiOiIiLCJhZnRlciI6IiIsIm5hbWVfZm9ybWF0IjoiZGlzcGxheV9uYW1lIiwibGluayI6Im9uIiwibGlua19kZXN0aW5hdGlvbiI6ImF1dGhvcl93ZWJzaXRlIn19@” portrait_url=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9hdXRob3JfcHJvZmlsZV9waWN0dXJlIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnt9fQ==@” quote_icon=”off” portrait_width=”125px” portrait_height=”125px” disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _dynamic_attributes=”job_title,portrait_url” _module_preset=”default” body_text_color=”#000000″ author_font=”||||||||” author_text_align=”center” author_text_color=”#008ac1″ position_font=”||||||||” position_text_color=”#000000″ company_text_color=”#000000″ background_color=”#ffffff” text_orientation=”center” module_alignment=”center” custom_margin=”0px|0px|4px|0px|false|false” custom_padding=”32px|0px|0px|0px|false|false”][/et_pb_testimonial][et_pb_text disabled_on=”on|off|off” _builder_version=”4.7.7″ _dynamic_attributes=”content” _module_preset=”default” text_text_color=”#000000″ header_text_align=”left” header_text_color=”rgba(0,0,0,0.65)” header_font_size=”20px” text_orientation=”center” custom_margin=”||50px|||” custom_padding=”48px|||||”]@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9jYXRlZ29yaWVzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiUmVsYXRlZCBjYXRlZ29yaWVzOiAgIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6ImNhdGVnb3J5In19@[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]